Susan O'Rourke | February 15, 2023

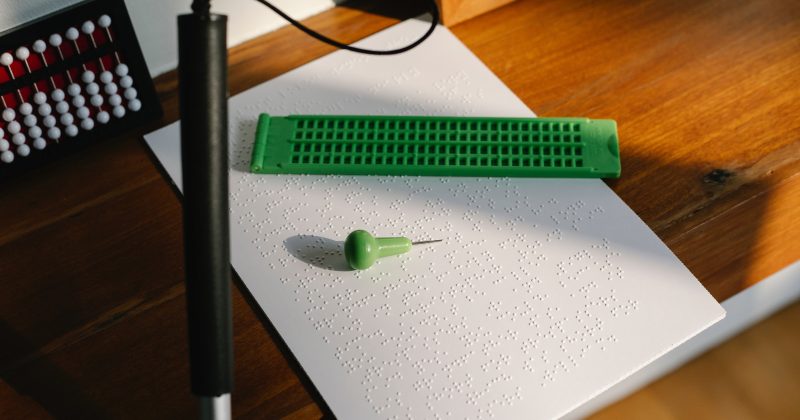

This winter, consider teaching students about a form of code that has been around since the 1820s: braille! Truly a global code, braille allows individuals around the world to read and write in many languages. Students may be surprised to learn that braille is not exclusively used in one language. As Sight Scotland explains, that’s because:

Braille is not a language. It is a tactile code enabling blind and visually impaired people to read and write by touch, with various combinations of raised dots representing the alphabet, words, punctuation and numbers. There are braille codes for the vast majority of languages – some symbols have different meanings for aspects such as accented letters, depending on the language. In its simplest form one letter is represented by one symbol, however contracted braille provides some shortening.

The American Federation for the Blind affirms that “Braille is used by thousands of people all over the world in their native languages and provides a means of literacy for all.” German speakers, for example, use a German Braille system that includes signs for letters, accents, and contractions used in German. Mandarin Braille, experts explain, “is a phonemic alphabetic representation….Translation of standard written Chinese into Braille can be divided into three steps: the first is segmentation of characters into words, the second is transformation from words to pinyin and the third from pinyin to Braille.”

Organizations and individuals around the world also have advocated for increased awareness of and accessibility for braille materials and technology. In 2021, for example, advocates and experts in Cameroon marked World Braille Day (January 4th) with both activities and a rally. Reporters noted that “blind demonstrators said the braille system helps them further their education, establish their independence and reduce the need for support” and called for greater support for educators to learn “braille in teacher training institutions.”

Of course, when discussing braille with students, it is important to avoid generalizations about individual reading and writing practices when discussing visual impairment. Sight Scotland emphasizes that “[n]ot all blind and visually impaired people use braille” and that “someone who loses their sight as an adult may prefer to stick to digital assistive technologies using specialist software such as screenreaders, video magnifiers or recorders.” Likewise, non-visually impaired individuals can also learn braille to communicate with others.

Check out the resources below to learn more about braille:

- Tips for Promoting Braille in the Classroom (Activities from the American Federation for the Blind)

- Sources of Braille Children’s Books and Magazines (The American Federation for the Blind)

- World Braille Usage (UNESCO)

- Braille Facts (Sight Scotland)

- Braille Trained Personnel Pushing for Education of the Blind in Nigeria (Video from CGTN Africa)

- Q&A: Everything you need to know about Unified English Braille (Perkins School for the Blind)

- Project INSPIRE: Spring 2023 (Perkins School for the Blind)

- Sharing braille with sighted classmates: A step-by-step guide (Perkins School for the Blind)

- An Overview of Braille around the World (Mobility International USA)

- Accessible Tourism: Why This Braille Railing in Naples Has Gone Viral