By Nicholas Allen | July 28, 2020

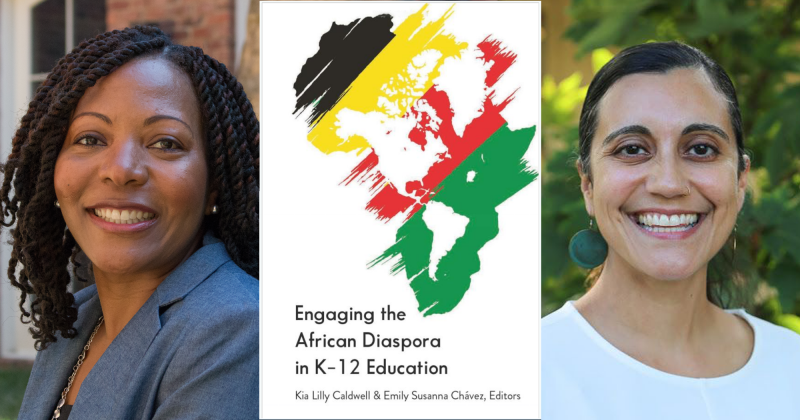

On April 3rd, 2020, the book Engaging the African Diaspora in K-12 Education by UNC-Chapel Hill’s Department of African, African-American and Diaspora Studies professor Dr. Kia Caldwell and Duke School’s Director of Equity and Justice Emily Chávez was published by Peter Lang Academic Publishers. The book is an edited collection of mixed chapters, containing scholarly research by respected names in the fields of African Studies, Afro-Latin American Studies, and African American Studies as well as curriculum resource guides by high and middle school educators.

The origins of the book began to take shape in 2014 when Chávez and Caldwell initiated the African Diaspora Fellows Program. The Fellows Program was a collaboration between nearly a dozen separate organizations that focused on empowering middle and high school educators to fill in the knowledge gaps left by alarmingly Euro-centric history curriculum in our schools. “A lot of people in the US don’t see how black communities are and have been historically connected to black communities in different countries. It’s not just parallel histories, but it’s also that these communities have been in dialogue with one another in shaping intellectual thought, in shaping self-determination,” stated Chávez about the inception of the program. The idea gained momentum, resulting in a 3-day professional development training intensive on African Diaspora communities in 2015 and a 7-day summer institute in 2016 entitled “Home, Community, and Belonging.” It also gained traction and support from Durham Public Schools, North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, eventually becoming the largest group effort in the history of the Consortium in Latin American and Caribbean Studies. Caldwell and Chávez also partnered with UNC-CH Women and Gender Studies Professor Tanya Shields’ and Department of Dramatic Art Professor Kathy Perkins’ Humanities in the Public Sphere grant effort as an outreach arm. The strength and success of the program served a vital need in education. Chávez emphasized,

“Not all teachers may have had the opportunity, or may not have seen the need to study African Studies, Afro-Latin American Studies, and African American studies in their college and graduate school experiences. I think that educators have a responsibility to serve their students equitably, and that means teaching black students and other students of color about their own histories. White students need to understand these histories as well.”

Caldwell reiterated that students (and teachers) have been denied knowledge about the movements and stories of people of color. Stories like that of the Haitian Revolution, which occupies two of the book’s chapters, one scholarly article and one curriculum guide, or the stories of Black Germans.

“I don’t think these [gaps in knowledge] are mistakes, I don’t think they’re coincidences. There’s a problem with what is taught about black history and how black history is defined and the kind of narratives that emphasize powerlessness and only oppression and not the way that black people have fought for their dignity and asserted their humanity.”

Caldwell and Chávez emphasized teacher leadership with the fellows (who intentionally came from all over the state) in an effort to spread this dialogue out into the schools, and this book is another expression of the effort of dissemination. Through both the fellows and the book, they aimed to appeal to North Carolina’s educational system from the top down; reaching administrators was an objective from the outset. Caldwell summarized,

“In assembling the book, we thought about teachers who had participated as fellows, school administrators, and the scholars–how could we bring all of them together to talk about ways to approach teaching about the African Diaspora, the importance of teaching about the African Diaspora, and also expanding it out of the United States since so many students aren’t introduced to African-descended populations outside of the U.S.?”

The multi-faceted nature of the book makes it a rich reference to teachers as they design lessons for their students on a burgeoning academic field. Chávez has already begun applying the resources of the book to her school. She offered a “Race and Racism: Study and Reflection” program for her colleagues which featured a few chapters from the book as key readings. The workshop consisted of four consecutive one and a half hour sessions. “There’s a need for that kind of work all the time, but I wanted to move with the momentum that people have had to re-analyze their own privilege, their own relationship to race and thinking about race, and their desire to create an anti-racist classroom and school.”

Chávez’s personal practice of implementation is also her hope for others. She expressed a profound sentiment that helps frame this work within the realities of life and keep it from the realm of abstraction: “My hope is that people put it into practice. I always say ‘social justice is lived.’ That’s what I believe and try to live by. I hope this becomes a really dynamic resource for people. Not just as a classroom application, but as something that sparks conversation.”

Engaging the African Diaspora in K-12 Education is available as a paper book and as an e-book. Caldwell and Chávez will be speaking during a virtual book launch for the book on July 30th. Find out more here.